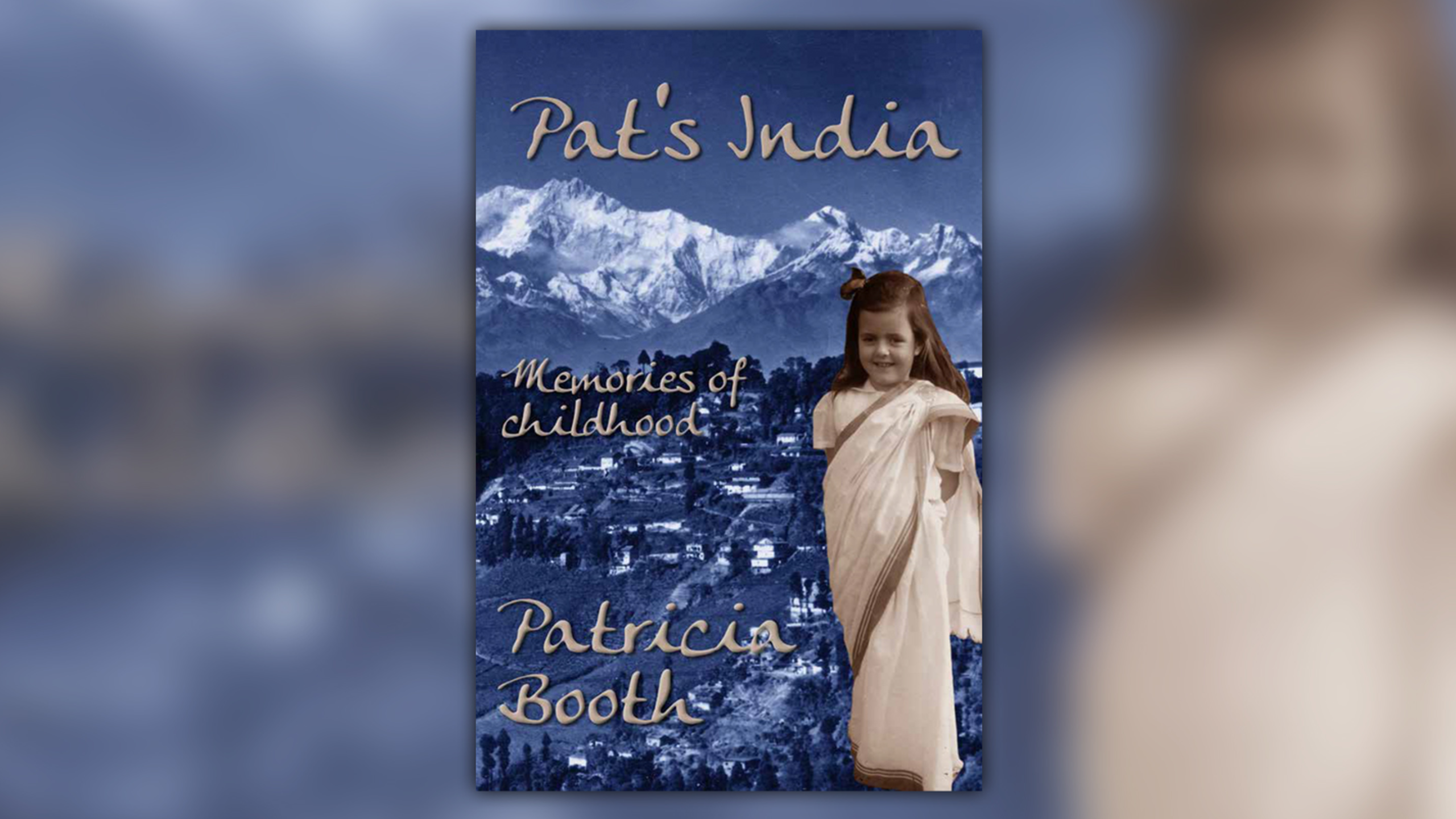

Patricia Booth. Philip Garside Publishing, $30* (p140)

ISBN number 978-1-927260-74-6

Baptists of a certain generation (mine) grew up with such names as St Paul’s School in Agartala and Mt Hermon School at least as familiar as those of the Baptist church in the next New Zealand town.

St Paul’s was founded by New Zealand Baptists in 1943, and continues today, in the Baptist mission compound in Tripura that was Patricia Booth’s home from her birth until she returned to New Zealand to study. She was, she records, the first European English-speaking child to live in Tripura state, where her father, Rev M J Eade, and mother had pioneered the Baptist work in the late 1930s.

Mt Hermon School was the church-based co-ed boarding school in Darjeeling, in the cooler climate of the foothills of the Himalayas, to which young Patricia Eade was sent for her schooling at the age of five, just a couple of years after Indian independence. Even just getting to and from school was a formidable journey. Many other children of New Zealand Baptist missionaries attended there over the years. Among its other alumni was the British playwright Tom Stoppard.

Patricia Booth’s new book was prompted by the posthumously-published autobiography of her mother, Cath Eade (In Heavenly Love Abiding, published in 2006). It captures vignettes of a happy childhood split between Darjeeling and Agartala in the late 1940s and 1950s, interrupted by the five-yearly sea trip to New Zealand (‘home’ in some senses, but not in others) for refreshment and deputation.

Boarding school clearly suited the author, and she appears to have relished the academic, artistic and social opportunities it provided, even as she hints at the challenges it posed for her parents, separated from two young kids for such long stretches. She tells of the cottage on the Mt Hermon estate, provided by the New Zealand Baptist Missionary Society (NZBMS) and known as Aotearoa, which allowed missionary parents to spend time with young children who were boarding.

The book offers a window on what is now, largely, a bygone era. At home in Agartala there was neither piped water nor electricity, and in 1947 a tiger had been shot just across the road from the compound. As a young child, the dreadful Bengal famine was fresh in the consciousness of the adults with whom she lived, and the transition to independence brought its own tensions and disruptions, including the new barrier between the NZBMS work in Tripura and that just a few kilometres away in East Pakistan. Booth recounts her father’s experience at Independence, sitting with a pile of blank Indian and Pakistani passports, helping villagers determine which country’s citizenship they would adopt.

At the other end of the social spectrum, there was the day the Maharajah, intrigued by the Anglo concept of a Christmas fruit cake, dropped by for afternoon tea. Patricia, aged 12, was left to host the Maharajah while her mother, having the spotted the car coming, rushed to shower and change. And there is her mother’s account of the young Maharajah’s wedding reception, to which both parents were invited.

It is a book of memories, letters and photos of a missionary kid’s childhood, rather than of insights on the mission work itself (for that there is the chapter on Tripura that her father wrote for the NZBMS centenary history). The book may appeal most strongly to friends and family of the author but I enjoyed the glimpses of her upbringing, of a world of which decades ago we heard so much, and of her own somewhat ambiguous relationship to both India, land of her birth, and New Zealand.

Review: Michael Reddell

*Also available as an e-book.