Early years

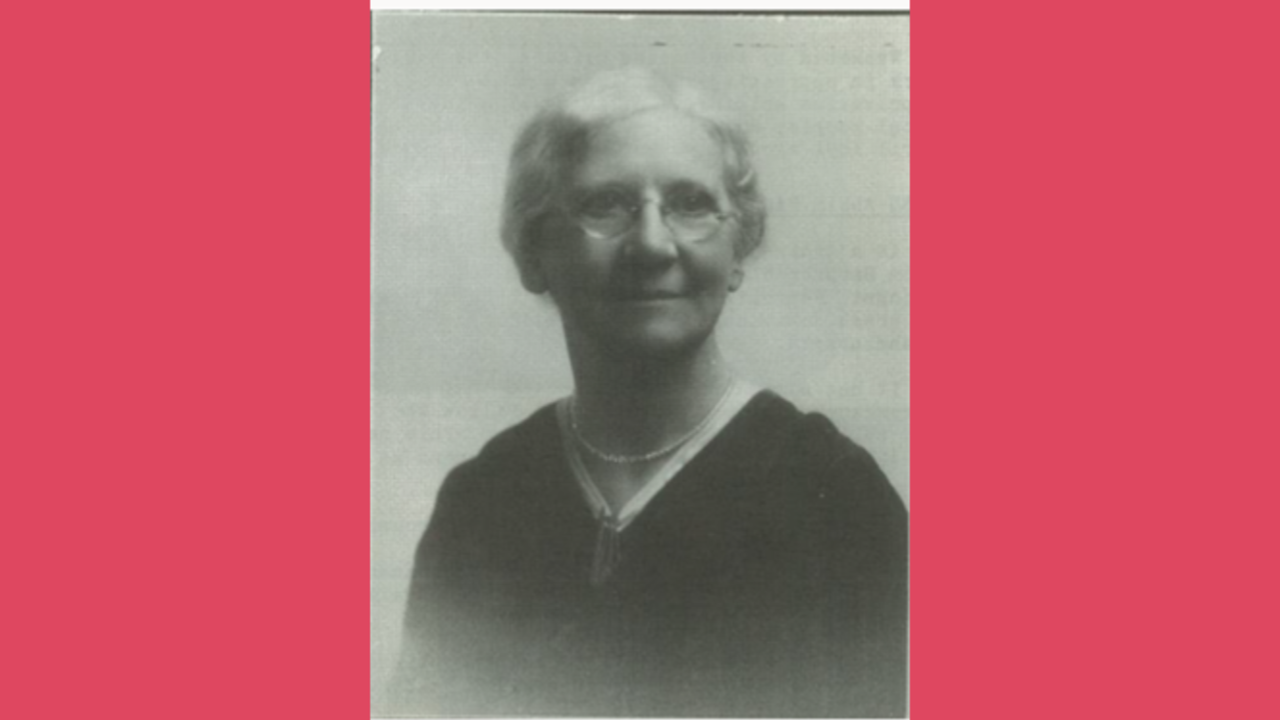

Following her birth in 1870 to Henry Beckingsale, a draper, and Sarah Bromley, Emma grew up in Dunedin. Her family were members at Hanover Street Baptist. Emma’s name is mentioned as signing the petition for enfranchisement of women in 1893. At that time she was living with her family in Park St, and working as a nurse.

There was strong missionary interest in the Baptist church and Emma was well acquainted with Rosalie Macgeorge, working in Bengal. Emma decided to offer her services too.

Missionary

After two years studying Bengali, Emma was arrived in Chandpur, on the huge Lower Meghna River, south of Dhaka, to do medical work. After doing this for eighteen months she left for her first furlough. After this, she went to work in a school and to reach out to women in zenanas. A year later, at the beginning of 1902, the mission decided it must place a medical worker in its Brahmanbaria compound, East of Dhaka. Emma moved there, and remained at Brahamanbaria, apart from furloughs, until she retired in 1935.

Emma’s years of service were marked by devotion to the people of Bengal. During her second furlough she collected funds for a dispensary which was erected on her return. (The dispensary was later incorporated in the hospital across the compound, and the building became an office.)

Emma Beckingsale conveyed well the conditions in Bangladesh in her writings in the NZ Baptist, describing the nature of missionary work among the women of India. In 1911 the Baptist Missionary Society published Gold of Tipperah a 90-page book by Emma describing the actions typical of the work she and her women colleagues did. She described the medical needs of a group of patients who had travelled to the foreign hospital: ‘They have charms on their arms and ankles, and tied in their hair. One boy has been cauterised on his side for fever. The daughter has a peg driven into her leg to let out the bad blood and cure indigestion. The old woman has been trying to cure rheumatism by having her hands and feet cut in fifty places with broken bits of glass. These strong measures have proved unavailing; they have decided to try the foreign medicine.’ In her account she mentioned the two women missionaries who had earlier died (Rosalie McGeorge and Hopestill Pillow) and the four who were forced to leave with broken health, and wrote:

We who are left know something of the strain of life in the enervating and depressing climate of Bengal, and of the patience and heart’s bold and strong crying to God with which even the veriest speck of gold or tiniest gem is won from the black, hard rocks of idolatry, bigotry and superstition for the adorning of the temple of our Redeemer.’

The position of child widows was extremely distressing for Emma and colleagues. Because girls were married at very young ages to men much older than themselves, wives very often out-lived their husbands, and, when they became widowed, found themselves unwanted and destitute. One Indian widow told Emma:

When one’s husband dies it is as though the light has gone out. One gropes in darkness, and is dazed and afraid, not knowing which way to turn or what to do. A widow is despised; no one cares, or helps or advises, or protects. Everyone is ready to rob and wrong her. No one but God knows the sorrows of a widow.

If they had little children their position was even worse, and many were forced to keep body and soul together by begging, or by prostitution. Children were often sold or seized for prostitution. Emma worked in the middle of all these problems that the mission had been combating from its earliest days. The stories were tragic—unwanted children brought by the police, who begged the missionaries to do something to save these little ones from probable prostitution.

For some years NZBMS used institutions set up by other missions, placing children for care with them. Then in 1917 Emma accepted more widows seeking shelter and offered them refuge on the mission compound. Three years later the mission gave official recognition of this work and established a home on land which missionary John Takle had purchased in 1919. NZBMS work raised the ground above monsoon flood level with bricks, a Brahmanbaria firm supplied bricks, tiles and roofing materials. Next steps were cottages for families, a store house for rice and vegetables, a cook-house, dining room and a weaving room. Later, dormitories were erected for older and younger girls. The number of women and children grew as more ‘unwanted babes of fallen women’ were taken in. Emma Beckingsale had responsibility for this home until she left India in 1934.

Roads were almost non-existent in Chandpur and Brahamanbaria. The mission owned no four-wheeled vehicle until the 1950s. The mission members and workers all travelled by bicycle or boat. Emma wrote: ‘In the rainy season the fields are flooded, and every little stream and canal is overflowing its banks. There are boats everywhere: large boats are laden with jute or rice, others with high crates of bamboo filled with earthen vessels on their way to the market, small dinghies taking boys to school, and men to their various occupations. Those covered with striped red and white cloth are bearing women and children to the house of some relation, for the rainy season is taken advantage of by all who can go a-visiting.’ The mission wanted a vessel for the use of its own workers and in 1898 the Baptist Sunday Schools of New Zealand raised more than 300 pounds to purchase a boat. It was named Shantimoni, meaning Jewel of Peace.

Over many years, missionaries and national workers travelled to small villages where they were able to talk about Christ. Emma’s participation in these activities was great. How busy she was may be seen in the following: ‘Last month I was out in camp, and am now at Nabinagar (an out-station). Next week I hope to spend at Chandpur, and after that look forward to a quiet spell in Brahamanbaria before the rains and more itineration work.’ Emma’s ‘quiet spell’ was a succession of busy days in the dispensary. For instance, in 1915, 1754 patients from 88 villages came to the dispensary, many coming more than once. She paid 216 visits to 110 patients in 34 villages. Similar figures could be cited for the following years up till she retired.

In the early twentieth century there was political agitation after Dhaka and Chittagong were placed under government control from Assam, though not Chandpur and Brahamanbaria where the NZ missionaries were. During many years the mission was held together by John Takle, Charles North and Emma Beckingsale. Emma had a staff of Bengali Bible women and teachers who worked with her.

One of Emma’s former colleagues later quoted Emma’s diary of 1928 when, after 31 years, the task was still enormous.

One feels overwhelmed by the tremendous task of trying to influence such numbers or turn them from their set ways or break up their superstitions or draw them away from their sin and error. One has to remind oneself constantly that God is Omnipotent and Almighty and that nothing is impossible with Him.[1]

Emma’s summary

We will finish Emma’s story by selecting from her own comments in the NZ Baptist of 1935 on the changes that could be seen after 50 years of NZ Baptist work in Bengal.

Fifty years ago in Tippera no railways, no missionaries, no knowledge of Christ…no girls’ schools and very few for boys… In the first schools we had to walk warily—Christians and Hindus must not sit together; Mohammedans and outcastes must not attend a Hindu school. In a Mohammedan school there must be no singing and no pictures… Many widows refused to drink medicine touched, by our hands.

When I first started zenana work forty years ago we were eager to have some of the ladies of the town visit us. We invited them and made all arrangements to bring them to the mission house in palkies, and promised that we would not offer them food and that there would be no men about the house. But no one came; they were afraid of public opinion.

Before I left Brahmanbaria last year the wife of a leading lawyer held a farewell party in my honour. Hindu and Mohammedan ladies were invited as well as Christians. We all sat down round a table and drank tea and ate biscuits and Indian sweets together. How we rejoiced to see this sign of progress…

Our Home and Orphanage is training fine young widows and girls for future useful lives; our orphan girls, as trained teachers and nurses, are helping in our mission schools and hospital. Our churches are growing in spiritual life. A Union of Baptist Churches connected with the Australian and New Zealand missions has been formed, and is working for self-support and development and also for the extension of Christ’s Kingdom through its own missionary society….

There is much still to do. We have only begun, but God’s Word is sure—”Have not I commanded thee? Be strong and of a good courage, be not afraid, neither be thou dismayed, for the Lord thy God is with thee.

Back in New Zealand

Emma remained active in church life. She also helped to found Ropeholders – a children’s ministry organisation that supported churches in encouraging children (and their parents!) to pray for and raise money for missionaries. The name came from a quote from William Carey: “I am willing to be lowered into the depths of the mine to dig, but remember, you must hold the ropes.”

Emma died on 5 April, 1955, in Dunedin.

Sources:

Edgar & Eade, Toward the Sunrise, P.38 ff.

NZ Baptist, 1935

Website of NZ History, https://nzhistory.govt.nz/suffragist/e-beckingsale

[1] NZ Baptist, May 1961, Quoted by Eileen Arnold.